|

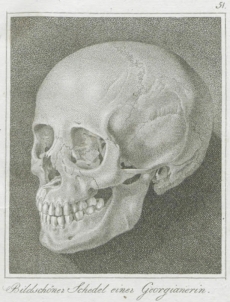

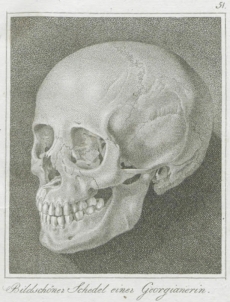

“Bildschöner Schedel einer Georgianerin”. Copper engraving from Blumenbach’s Abbildungen naturhistorischer Gegenstände, Vol. 6 (1802) No. 51. Click on the picture to enlarge. Following contemporary travelogues, Blumenbach attributed special beauty to the inhabitants of Georgia, cf. ; vgl. Figal, Sara: ”The Caucasian Slave Race: Beautiful Circassians and the Hybrid Origin of European Identity.” In: Lettow, Susanne: Reproduction, Race, and Gender in Philosophy and the Early Life Sciences. Albany: SUNY, 2014, pp. 163–186. Digital version.

|

|

Blumenbach is located at the beginnings of a debate in modern society that continues today about the origin of life, the origin of species, monogeny, polygeny, and indeed the issue of race. On the basis of his collection of skulls, he proposed a famous classification of human varieties. By additionally arguing for the unity of humankind, Blumenbach became the founder of scientific anti-racism. This fact is less known, and the project is intended to make also this major contribution of Blumenbach to science and society more visible.

Specifically, our critical editing of Blumenbach’s doctoral dissertation De generis humani varietate nativa (1775 and later editions) will throw new light on the origins of anthropology, on anthropology’s disentanglement from biblical-sacred history, and also from the humanistic-philosophical orientation which was prevalent during the Enlightenment, and on its development towards a more strongly naturalistic-scientific approach. |

|

Further reading |

|

Junker, Thomas: “Johann Friedrich Blumenbach und die Anthropologie heute.” In: Gurka, Dezső (ed.): Changes in the image of man from the Enlightenment to the age of Romanticism. Philosophical and scientific receptions of (physical) anthropology in the 18–19th centuries. Budapest: Gondolat Publishers, 2019, pp. 125–142. Digital version. |

|

Rupke, Nicolaas A.; Lauer, Gerhard: “Introduction: A brief history of Blumenbach representation.” In: Rupke, Nicolaas; Lauer, Gerhard (ed.): Johann Friedrich Blumenbach: Race and Natural History, 1750–1850. London und New York: Routledge, 2019, pp. 3–15. Digital version on author’s hompepage. |

|

On Blumenbach’s contributions to anthropology see also |

|

• chronological list of Blumenbach’s publications on physical anthropology |

|

• research literature on the subject “Blumenbach and anthropology” (select bibliography) |

|

• lecture videos of the conference “Johann Friedrich Blumenbach and the Culture of Science in Europe around 1800” (2015). |

|

|