|

|

|

Catalogue of the so-called “Schlütersche Mineraliensammlung” |

Scope of the donation of 1777

Structure of the catalogue

Leibniz fossils Göttingen University Library and Academic Museum around 1800. Watercolour by Johann Christian Eberlein (1778–1814); detail. Click for larger view and explanations. Göttingen University Library and Academic Museum around 1800. Watercolour by Johann Christian Eberlein (1778–1814); detail. Click for larger view and explanations. |

|

| Blumenbach context |

| In 1777, the Royal Library in Hanover donated numerous mineralogical, geological and palaeontological objects to the Academic Museum of the University of Göttingen. Blumenbach was in Hanover in April 1777 to carry out the takeover formalities and organise transport (cf. Dougherty, Frank William Peter: The correspondence of Johann Friedrich Blumenbach. Rev., augm. and ed. by Norbert Klatt. Volume 1. Göttingen: Klatt, 2006, Letter No. 60 (2 Apr. 1777); official correspondence on the handling of the donation ibid., letters No. 51–64 (9 Jan.–23. May 1777)). The approximately 1,600 objects donated to Göttingen are already included in the “Catalogus” of the Academic Museum compiled by Blumenbach in 1778. They represent about 13 percent of its contents (more than 12,000 catalogue numbers). |

| There is a catalogue to the collection which was compiled at an unknown time, but apparently before the objects were handed over to the Academic Museum (today: Niedersächsisches Landesarchiv Hannover, NLA HA Hann. 92 Nr. 1016). A comparison with Blumenbach’s “Catalogus” allows to determined the provenance of numerous objects in the Academic Museum and in today’s Göttingen University Collections. The project “Johann Friedrich Blumenbach – online” makes a digital copy of the catalogue available online (with the permission of the Niedersächsisches Landesarchiv Hannover). |

| Open or download digital version (28 MByte). |

|

Blumenbach context

Structure of the catalogue

Leibniz fossils |

|

| Scope of the donation of 1777 |

The objects donated to Göttingen University in 1777 came mainly from the collection of the Goslar metallurgist and mining expert Christoph Andreas Schlüter (1668–1743), the so-called “Schlütersche Mineraliensammlung” (Schlüter Mineral Collection). It had been purchased in 1750 for the Royal Library in Hanover (cf. Dougherty, loc. cit., Letter 56). As early as 1759 the Göttingen professor and library director Johann Matthias Gesner (1691–1761) had suggested its use as a teaching collection for the University of Göttingen (cf. Nawa, Christine: Sammeln für die Wissenschaft? The Academic Museum Göttingen (1773–1840). Göttingen, 2010, p. 43; digitised version). The collection comprised 1595 metal and mineral samples.

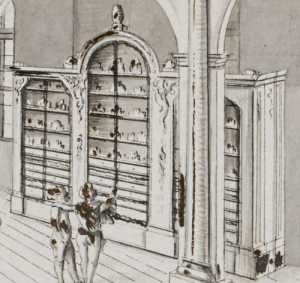

The donation included also at least one large cabinet for storing the collection (Dougherty, loc. cit., letter No. 54; in letter 56 several cabinets and containers are mentioned). A copy of the “Catalogus” of the Academic Museum made by Blumenbach contains two pen drawings with interior views of the museum. One of the drawings also shows the cabinet from Hanover. Apart from three vitrine-like zones with a total of 13 shelves, it has 36 drawers. These could be the 36 drawers listed in a table of contents of the catalogue of the collection (see “Structure of the catalogue”). In the Academic Museum, the cupboard no longer served to store the Schlüter Collection, which was not set up separately but integrated into the museum’s order and storage system. According to the caption of one of the drawings, in Göttingen the cabinet served for storing “Gypsartige […] Kieselartige […] [und] Thonartige Steine”.

The Academic Museum was given also a particularly valuable silver specimen purchased in 1730 for the Royal Library in Hanover (Dougherty, loc. cit., Letter No. 57 (5 March 1777)), which was stolen from the museum in January 1783 (Nawa, loc. cit., pp. 73–74; digitised version).

|

|

|

Cabinet in the Academic Museum. Pen drawing from a copy of the “Catalogus” of the Academic Museum (London, British Library, London, King’s Mss. 394, fol. 4r), made in 1778.

In a caption, loc. cit., fol. 3r, this cabinet is described as “der große Schrank aus der Bibliothek zu Hannover” (the large cabinet from the library of Hanover). Probably it is the cabinet made in Hanover for the storage of the Schlüter Collection and donated to Göttingen in 1777. |

|

|

Blumenbach context

Scope of the donation of 1777

Leibniz fossils |

|

| Structure of the catalogue |

| The catalogue has 45 sheets written on both sides (modern foliation: 48 to 92; fol. 92v empty). The objects are listed in tabular form with a short description and the indication of origin and weight, which enables their identification in later collections and collection catalogues. |

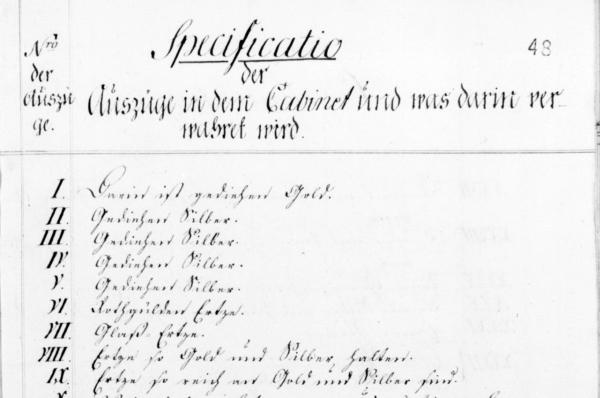

| The catalogue begins with a list of 36 drawers, marked with Roman numerals, of a cabinet in which the collection was kept (”Specificatio der Auszüge in dem Cabinet und was was darin verwahret wird” [index of the drawers of the cabinet and what is stored in them]). Each drawer contains samples of one or more metals or minerals in various forms: drawers I to XXXIII contain metals or metalloids (gold, silver, lead, copper, tin, mercury and cinnabar, iron, antimony, bismuth, cobalt), drawers XXXIV to XXXVI minerals (alum, vitriol, sulphur, “Blenden”, asbestos, petrified wood, “Stein-Marck” (nacrite), “Galmei”, rock crystal, garnet, amethyst, carnelian). |

Specificatio der Auszüge in dem Cabinet und was darin verwahret wird.. First page of the catalogue of the „Schlütersche Mineraliensammlung“, Niedersächsisches Landesarchiv Hannover, NLA HA Hann. 92 Nr. 1016. Click to open the complete index (PDF, 28 MBytes). Specificatio der Auszüge in dem Cabinet und was darin verwahret wird.. First page of the catalogue of the „Schlütersche Mineraliensammlung“, Niedersächsisches Landesarchiv Hannover, NLA HA Hann. 92 Nr. 1016. Click to open the complete index (PDF, 28 MBytes).

|

However, the following pages do not contain 36, but more than 49 tables for a total of 56 “Auszüge” (drawers). The contents of some drawers are not listed in a separate table, but within other tables, preceded by the note “No.” and (mostly) Arabic number (e.g. “No. 30” within table “XXIX”; “No. 31” within table “XXII” [read “XXXII”]). The order of the substance classes in the “Specificatio” and in the table section of the catalogue is identical, and also the designations of the drawer contents in the table headings are the same, except for a few, only linguistic variants. The higher number of drawers in the table section of the catalogue results from the fact that some substance classes take up more “Auszüge” than are indicated in the “Specificatio” (cf. PDF file with synoptic table).

The fact that the 56 tables are in principle based on the drawers of one or more pieces of furniture can be seen, for example, from an addition to Table LIV (fol. 92r): “NB. Von Nro 13. bis zu Ende liegt oben in der LIII Lade.” (NB. From No. 13. to the end lies above in the LIII drawer.) The meaning of the addition “In the lowest part” or “In the highest part” to some titles both in the “Specificatio” and in the table part of the directory is unclear. Perhaps it is a reference to the upper, vitrine-like part of the storage cabinet (see above) and its lower part with the drawers. |

| Table headings: a Roman number and an indication of the substance class to which the samples belong (“In diesem Auszuge ist/sind […]“ (In this excerpt is/are […]). If a table runs across several pages, the complete heading is repeated on the following pages [exception: table L, with three different titles]. |

|

In one case, the order of the tables is incorrect (Table IV is shown after Table V; at the top of fol. 52v, 53v and 54 with Tables V and IV there is the note “NB Ist versetzt.” [NB Is offset.]). Some table numberings are obviously incorrect: they lack a Roman numeral (for example a third “X” in “XXVII” (fol. 78v) (instead of “XXXVIII”) after “XXXVII”; and after “XXIX” (fol. 72v) “XXII” and “XXIII” instead of “XXXII” and “XXXIII”) or they are otherwise incorrect (e.g. after “XXV” (fol. 69r) “XIX” instead of “XXVI”).

Also the Roman number of the last table is probably incorrect (after the tables “LIV [...] Galmeyen” and “LV” follows again a table marked “LIV” with samples of “Granaten, Kristallen, Amethisten, Carneolen und andere Steine”, which should have the correct number “LVI”). Altogether 56 “Auszüge” are listed. |

|

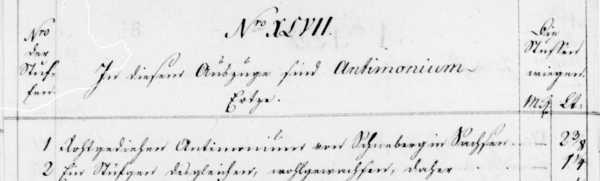

| The tables have three columns: column 1 („Nro der Stuffen“ [No. of the sample]) contains a consecutive object number for the samples of the same material type. If a drawer contains samples of different materials, there are several number series beginning with “1” in the table (e.g. Table I and LIII); likewise, in some cases the counting runs across several drawers if they contain samples of the same substance (e.g. II and III, VI and VII, VIII and IX [= VIIII]). Table column 2 contains a name or description of the sample and the place where it was found. Column 3 (”Die Stuffen wiegen”) shows the weight of the sample in the old German units of weight “Mark” and “Lot”. |

| For the identification of the objects in Blumenbach’s “Catalogus” of the Academic Museum from 1778, the descriptions in column 2 of the table are of importance, some of which Blumenbach has taken over literally. In addition, labels exist for some objects (by Blumenbach’s hand or from later times) with a description and an inventory number, formed from the (sub)collection code “Schlüter”, the Roman table number and the serial number in column 1 of the tables (e.g. “Schlüter LV.33” for a rock crystal, today Göttingen, Geosciences Collection, GZG HST 0.023). The weight data were neither included in the “Catalogus” nor in the labels. |

Beginning of Table XLVII of the catalogue of the „Schlütersche Mineraliensammlung“. Niedersächsisches Landesarchiv Hannover, NLA HA Hann. 92 Nr. 1016, fol. 85v. Beginning of Table XLVII of the catalogue of the „Schlütersche Mineraliensammlung“. Niedersächsisches Landesarchiv Hannover, NLA HA Hann. 92 Nr. 1016, fol. 85v.

The sample Nos. 1 and 2 are described as „Rohtgediehen Antimonium von Schneberg in Sachsen[;] 2 3/8 Lot“ (Red Antimony [Kermesite] from Schneeberg in Saxonia; 2 3/8 Lot) and „Ein Stüfgen desgleichen, wohlgewachsen, daher[;] 1 1/4 Lot“ (A smalll sample of the same, well formed, from the same place; 1 1/4 Lot). |

|

Blumenbach context

Scope of the donation of 1777

Structure of the catalogue |

|

| Fossils from the collection of Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz |

| Among the objects donated in 1777 were also a few fossils from the natural history cabinet of Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz (1646–1716), cf. Reich, Mike; Gehler, Alexander: „Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz’ Sammlung geowissenschaftlicher Objekte. Eine Spurensuche“. In: Wellmer, F. W. et al. (Hrsg.): Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz. Protogaea sive de prima facie telluris et antiquissimae historiae vestigiis in ipsis naturae monumentis dissertatio. Hildesheim, Zürich, New York: Olms-Weidmann, 2014, pp. LIX–LXX. Blumenbach referred to the Leibniz fossils as early as 1778 in a description of the donation: |

|

Im Jahr 1777 ist auf Ihro Majestät Befehl, auch die Mineralien-Sammlung, die bis dahin auf der Bibliothek zu Hannover gestanden, mit dem akademischen Cabinet verbunden worden. Diese ist vorzüglich wegen der zahlreichen Gold- und Silber-Stufen, und wegen der vielen seltnen Spatdrusen von ausserordentlicher Größe, schätzbar. Unter den Silberstufen ist unter andern ein Stück gediegenes Silber mit etwas Rothgülden, was blos am innern Werth gegen 1700 Rthlr. hält: und unter den Kalk- Gyps- und Fluß-Spaten finden sich alle Arten, die seit hundert Jahren auf dem Harz gebrochen worden. Theils rührt diese Collection von dem großen Mineralogen Schlüter, theils aber vom Herrn von Leibnitz her, der verschiedne der hier befindlichen Petrefacte in seinen Protogäis beschrieben und abgebildet hat.

From: „Etwas vom Akademischen Museum in Göttingen“. In: Göttinger Taschen-Calender: für das Jahr 1779. Göttingen: Dietrich: [1778], pp. 45–57, here p. 52 (01012).

(In 1777, on His Majesty’s order, the mineral collection, which until then had stood in the library in Hanover, was given to the Academic Museum. This collection is particularly valuable because of the numerous gold and silver specimens, and because of the many rare spar druses of extraordinary size. Among the silver specimens there is, among others, a piece of solid silver with some “Rothgülden”, which is worth around 1700 Reichsthalers: and among the limestone, gypsum and river spars there are all kinds that have been broken on the Harz for a hundred years. Parts of this collection come from the great mineralogist Schlüter, others from von Leibnitz, who described various fossils in the collection and gave illustrations of them in his Protogäis.) |

|

So far, three of these fossils have been identified in the geoscientific collections of the University of Göttingen: a fossil oyster from Worchestershire/England (today Göttingen, Geowissenschaftliche Sammlung, GZG HST 0.445), a fossil horsetail (GZG HST 00916; shown in Beisiegel, Ulrike (Hg.): Die Sammlungen, Museen und Gärten der Universität Göttingen. Zweite Auflage. Göttingen: Universitätsverlag, 2018, p. 138; online version.) and the molar tooth of a woolly mammoth (GZG HST 0.500; shown in Reich, Mike; Gehler, Alexander: “Giants’ Bones and Unicorn Horns”. In: Georgia Augusta. Wissenschaftsmagazin der Georg-August-Universität Göttingen, English edition 8 (2011)(digitised version), pp. 44–50, p. 48. The molar is shown in a copperplate engraving (Tab. XII) in Leibniz’s work Protogaea: sive de prima facie telluris et antiquissimae historiae vestigiis; digitised version, published posthumously in 1749. Other Leibniziana from Göttingen identified as early as 1937, including original illustrations, were destroyed in the explosion of an evacuation depot in 1945 (cf. Reich and Gehler, 2014, p. LXIII).

The fact that the Leibniz objects became part of the Schlüter Mineral Collection can possibly be traced back to the Hanover aulic councillor and librarian Christian Ludwig Scheidt (1709–1761). Scheidt was the editor of the Protogaea, and he was librarian at the Royal Library in Hanover from 1748 and involved in the purchase of the Schlüter Collection in 1750 (cf. Dougherty, loc. cit., Letter 56).

|

|

|

|